In the March issue of the women’s newspaper Newaya Jin the journalist Füsün Erdoğan, who herself spent eight years in a Turkish prison on terror charges, writes about the history and present of hunger strikes as a means of struggle.

Hunger strikes and death fasting are historical means of struggle. If in this day and age this weapon is mainly used by prisoners in many parts of the world, it has also been a general form of action by individuals and groups against injustice in history.

Before Christianisation it was a common mechanism in Ireland to protest against injustice with hunger strikes. This action, called “Troscadh” or “Cealachan”, was carried out by the person directly on the doorstep of the person who had caused the injustice. In Ireland it is considered a great disgrace to homeowners when there is a hungry person in front of their house. A similar tradition exists in India. If someone goes on a hunger strike in front of a house, it means calling for justice to be done to society and for judicial mechanisms to be set in motion. This tradition goes back to 750 BC and was banned by the English colonialists in 1861. Among English and US women’s rights defenders, this form of action developed into a clear form, just demands on the authority to exercise political power.

Hunger strikes in women’s struggle for the right to vote

Born in 1864 in Scotland, Inverness, Marion Wallace Dunlop was one of the leading defenders of women’s rights. Dunlop was an active member of the Social and Political Women’s Union (WSPU), which promoted the right to vote and equality in society, and was arrested and detained twice in 1908 on charges of disrupting harmony in society. When she was imprisoned in Holloway Prison in July 1909 and deprived of her legally guaranteed rights, she began a hunger strike.

Dunlop’s hunger strike, the first in the prisons of England, lasted 91 hours. She was then released by the English administration because of her poor health. This form of action was quickly adopted by the WSPU as a peaceful protest against repression. In September of the same year, the British government passed a law on the forced feeding of prisoners on hunger strike. Based on this law, Mary Jane Clark, sister of the leader of the English women’s movement Emmeline Punkhurst, died in 1910 as a result of the health damage caused by forced feeding during her hunger strike.

In the USA, women’s rights activist Alice Paul began a hunger strike in the Occoquan Workhouse, Virginia, to fight for women’s right to vote. This action went down in history in 1917 as the first hunger strike of women activists with political demands.

Hunger Strikes in Turkey and Northern Kurdistan

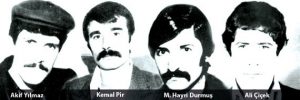

In Turkey and Northern Kurdistan hunger strikes and death fasting have always been an expression of the uprisings against the oppression of the state in the dungeons. After the hunger strike of the poet Nazım Hikmet in prison, PKK prisoners in the dungeon of Amed (Diyarbakır), the heart of Northern Kurdistan, started an unlimited hunger strike – a so-called death fast – against inhuman and degrading torture for the first time on 14 July 1982. In this first death fast, which must be regarded as one of the turning points in Kurdish politics, the leading PKK cadres Hayri Durmuş, Kemal Pir, Ali Çiçek and Akif Yılmaz lost their lives. Witnesses of these days say: “There was a war of will and the people won this war together with those who used their bodies”.

On April 11, 1984, prisoners from Devrimci Sol and TIKB trials began a hunger strike for an end to institutional dressing, torture and the rights of political prisoners as well as social and human prison conditions. The hunger strike was transformed into a death fast by 400 prisoners on the 45th day. Between the 60th and 70th day of this resistance Abdullah Meral, Haydar Başbağ, Mç Fatih Öktülmüş, Hasan Telci lost their lives. In particular, the hunger strike finally ended with the withdrawal of the prison clothing requirement in February 1986. Aysel Zehir, who was accused in a TIKB trial, had taken part in this hunger strike as a death fasting prisoner. She was chained to her bed in the hospital room and refused any medical treatment. Every time she regained consciousness, she ripped the cannulas through which she was given a serum out of her arm. Through coercive treatment she is sentenced to live with Korsakov’s syndrome.

The first in death fasting: Ayça İdil Erkem

While in the 1990s hunger strikes were used as a method of struggle to obtain rights by various opposition circles, it remained a main method of prisoners to fight the repression and oppression policies of the state. Women took part in all these resistance actions in large numbers.

An indefinite hunger strike was started in 43 prisons to repeal the “May Decree” of Justice Minister Mehmet Ağar of 1996, who was in office under the coalition government of Necmettin Erbakan and Tansu Çiller. Apart from seriously ill prisoners, all female and male prisoners took part in the hunger strike. On the 45th day, the action was transformed into a death fast in which 355 prisoners, including many women, took part. Ayça İdil Erkem was – as far as known – the first fighting woman worl

dwide and in Turkey to lose her life in death fasting. She died on the 68th day of her resistance. Ayça İdil, who burned herself into the collective memory with her fearlessness, became a symbol of the women’s liberation struggle.

Of seasons, years and immortality…

Against the introduction of isolation prisons, the so-called F-type prisons, prisoners from the DHKP-C, TKP/ML and TKIP procedures began a hunger strike on 20 October 2000, which they converted into a death fast one month later.

On 19 December 2000, the Turkish state carried out a massacre in the prisons and transported the political prisoners to the F-type prisons, whereupon the death fast expanded. What made this action different from all previous ones was the fact that women participated in it on a massive scale for months to years. Within the framework of this death fast, which lasted from 2000 to 2007 with ever new groups, 25 women were killed. Outside the prisons, six women died participating in the death fast started by TAYAD. Hundreds have to live with the Korsakov syndrome due to the coercive measures of the state.

Hunger strike against solitary confinement

On 12 September 2012, 483 PKK and PAJK prisoners started a hunger strike demanding the lifting of Abdullah Ocalan’s total isolation and the free use of the Kurdish language. This hunger strike ended on the 67th day with the fulfilment of the demands. Among the 483 hunger strikers, the proportion of women was considerable. Prisoners who were taken to hospitals after the end of the hunger strike were exposed to serious problems there. Among other things, prisoners were kept waiting a long time near the deceased.

Nuriye slurry, Esra and Semih Özakça

Following the declaration of a state of emergency in 2016, thousands of public sector workers were dismissed. Academic Nuriye Gülmen and teacher Semih Özakça then went on hunger strike on 8 March 2017 under the slogan “We demand our work back”. When both were arrested on the 75th day of the action, another teacher, Esra Özakça, took up the hunger strike. She stopped her hunger strike on the 70th day because of heart problems. Nuriye Gülmen and Semih Özakça ended their action on 26 January 2018, the 324th day of their hunger strike.

A woman in the footsteps of 14 July: Leyla

Leyla Güven picked up the trail of those who started their hunger strike in the dungeon of Amed on 14 July 1982 when she declared during her trial on 7 November 2018 that she was going on an indefinite hunger strike to break the isolation of the representative of the Kurdish people, Abdullah Ocalan!

Once again, history has imposed the mission of leadership on the women and Leyla had agreed this with herself, told no one around her of her decision and raised her hand on the day of the trial.

She was born in 1964 in Konya (Cihanbeyli, Yapalı) as a Kurdish woman from Central Anatolia. Because the family wanted it that way, she was married to her cousin at the age of 17. The marriage lasted five years. After the divorce she left Germany with her two children and returned home. After raising her children and building her own existence, she devoted all her time to political work and became a candidate for Konya in 1999. In 2001 she went to Ankara and took over the management of the women’s structures at HADEP Head Office. As a member of the Party Council, she held this position until 2004.

In the 2004 local elections she was elected mayor of the municipality of Küçük Dikili in Seyhan County near Adana. After five years as mayor in the municipality, she was elected mayor of the district town of Wêranşar (ViranşehirI in the province of Riha (Urfa)) in the 2009 local elections. After eight months in office, she was arrested as part of the political extermination campaign known as the KCK Operation. Together with thousands of politicians, she was held in Amed prison for five years. In the parliamentary elections on 7 June 2015, she ran again for the HDP in Riha and was elected a member of the Turkish National Parliament. She was not re-elected in the new elections on 1 November 2015, which were announced arbitrarily by Erdoğan and took place under great pressure of repression. However, Leyla Güven has never suspended her women’s and other political work and on 26 March 2015 she was elected co-chair at the extraordinary congress of the DTK (Democratic Congress of Societies).

Because Leyla made a statement against the Turkish state’s occupation attack on Efrîn, she was arrested in Amed and arrested again on 31 January 2018. After years of struggle and resistance, she was aware that this dynamic would bring her step by step towards freedom: “The identity of an organizing, institutionalizing, fighting woman was created in Kurdistan thanks to the freedom ideas of Abdullah Ocalan. That’s why I, as a Kurdish woman, found myself in it, strengthened my will and appropriated this identity.” This is precisely the origin of their secret to go on hunger strike for the breakthrough of total isolation.

Leyla’s resistance is everywhere

Leyla’s resistance has expanded from the prisons in Turkey and Northern Kurdistan to Europe, the Middle East and Kurdistan. PKK and PAJK prisoners in nine prisons in Turkey and Northern Kurdistan were the first to start an indefinite hunger strike on 16 December 2018. Of the 40 prisoners in this first group, twelve were women. Already in the following days these numbers multiplied and the action grew to 300 persons.

To make Leyla’s resistance heard in Europe and the world, 14 people, including a former member of parliament, an academic, a journalist and a politician, started an indefinite hunger strike on 17 December 2018 in Strasbourg and became the centre of the actions taking place in Europe.

On the 65th day of Leyla’s resistance, the Turkish state let the representative of the Kurdish people, Abdullah Öcalan, speak with his brother Mehmet Öcalan. Since the state used such games instead of responding to the demands of the prisoners on hunger strike, it could not convince Leyla or the other hunger strikers.

At the beginning of her action Leyla had said “until the break of isolation” and the isolation continues. On the 79th day of her action, 25 January 2019, Leyla was suddenly released in her trial, which went down in history as an attempt by the state to break the hunger strike. On that day all eyes rested on Leyla and Leyla once again declared that she was continuing her action. Leyla is determined to continue her action until blind eyes can see again, deaf ears can hear again until Öcalan’s isolation is lifted.

When Leyla started her action, we were in the first week of November, the season changed, winter came, days, months passed… January was over, February halfway. In the days I write this, Leyla was admitted to hospital (98th day); as she refused treatment, she was taken home. Her body resists hunger with every cell. Her daughter Sabiha stresses that her mother is on hunger strike “for life and for letting go”.

While Leyla in Amed resists with every cell of her body, hundreds of prisoners in the dungeons, Nasır Yağız in Erbil, Imam Şiş in Galler, 14 activists in Strasbourg, Yusu Iba in Canada, Toronto, Sebahat Tuncel and Selma Irmak in prison Kandıra, Fadile Tok, member of the Women’s Council Iştar in Mexmûr, resist, it is our task outside to broaden the resistance.

First published in the March issue of the women’s newspaper Newaya Jin, written by journalist Füsün Erdoğan in Turkish