An internationalist who has come from his flat native country to meet the people of the mountains, to learn and share the most inspiring revolution of the 21st century wrote an embodied narrative, relating impressions of daily life and the latest tragic events with this upsurge of the Turkish threat on Rojava. The hope of making close what, too often, seems far away while what is played out here, in reality, concerns us all.

It’s 7.45am on this Monday morning, it’s now a bit chilly now, but if the sun comes out, which it often does, too often, at midday, the atmosphere still gets quite warm. I have been walking this fifteen-minute walk every day for a few weeks now, skirting the outskirts of this small town

where the precariousness jumps out at times, while it rubs shoulders with buildings that are a little better off. Concrete is, unfortunately, undisputed king here, with skeletons of future buildings dotting the landscape without concern for aesthetic considerations. On this bright day, the mountains on the Turkish side sit majestically on the horizon like an inaccessible invitation.

Zigzagging between a few old tractors, guilds of chickens and columns of geese, in a colourful setting that could be used for a Kusturica film. The boundaries between town and country are blurred in these peripheral urban areas. I make my way to what has recently become my “workplace”: a large cream-coloured building, in a very poor state of repair, a former secondary school of the Syrian regime, which today houses the bilingual (Arabic/Kurdish) school administration for the 87 schools in the small town and the many surrounding villages. This morning, there is a calmness worthy of a Friday (which here has the character of a Sunday) that makes me think that I will probably find the door closed. This Monday is not a Monday like any other. Mourning and commemoration are the order of the day. Two nights ago, Turkish bombs sowed death in a region historically rather unscathed compared to others.

This Monday is not a Monday like any other. Mourning and commemoration are the order of the day. Two nights ago, Turkish bombs sowed death in a region historically rather unscathed compared to others.

On the night of 20-21 November, at around midnight, an airstrike targeted the village of Teqil Beqil, killing two people and destroying a power plant. A group of people rushed to the scene to help the victims and issued a statement denouncing the incident. A journalist from a local media

accompanied them. Three more rounds of macabre shells then fell on the assembly, killing nine people. These “double-tap” strikes is a strategy as common as it is despicable on the part of the red-flagged air force adorned with a moon and a white star. The aim is undeniable: to kill by

creating psychological shock. It is impossible not to see the sordid hypocrisy of the Turkish Defence Minister who dares to speak of “surgical strikes against specific military targets”. Of course, if the reasoning is to consider any civilian, in solidarity with the popular self-defence forces, as a

terrorist, this opens the way to a pseudo-legitimisation of many war crimes.

Yesterday morning, the mood among my colleagues was one of gravity and apprehension. On 20 November, International Children’s Day, a big parade was planned in the city, followed by a party with several schools. I had attended a dress rehearsal at one of the schools. The children were proud to show me the songs and dances they had prepared for the occasion. This year there will be no celebration, the neighbouring army has decided to replace it with stupefaction and grief. The traditional collective coffee/tea at the beginning of the day drags on, everyone exchanging news of the tragic events. News arrives in the course of the morning revealing the number and identity of the colleagues killed during the night. Colleagues learn that people close to them are among the dead. I watch helplessly as they grieve. I don’t know where to stand, what to do, what to say. I content myself with being there, a discreet witness, a stranger in spite of everything. I think of the magnitude of the damage and the pain caused by the interests of a minority willing to carry out the most sordid tricks to stay in power.

If Erdogan and his gang of murderers are playing the escalation card, it is not in the supposed defence of their threatened people, but because of their disastrous political record and the approaching elections. It never ceases to amaze me that the old strategy of creating an external enemy to deflect responsibility from the elites for the sad fate of the people still works, that it remains, despite the lessons of history, as yet insufficiently learned, frighteningly effective. And no matter how crude the make-up, the media will play its role as a sounding board, refraining from “taking sides”, which is enough to give credence to the lie. It had been a long time since I had heard ‘sehid namirin’ (martyrs never die) sung and chanted with

a heavy heart. The collective funeral of the eleven victims was attended by a large crowd, filled with emotion and rage from beginning to end. The people killed were particularly appreciated and recognised for their longstanding involvement in civil society. Their rapid presence at the scene of the attack, in the middle of the night, was a reflection of their constant dedication to supporting the collective construction of this revolutionary democratic alternative. Two of them were, for example, very active in the ” Martyrs’ House “, which provides support and assistance to bereaved families. I met them. They were the first dead people I met in life, which makes this murderous rampage, which has been accelerating for several months now, even more concrete and tangible.

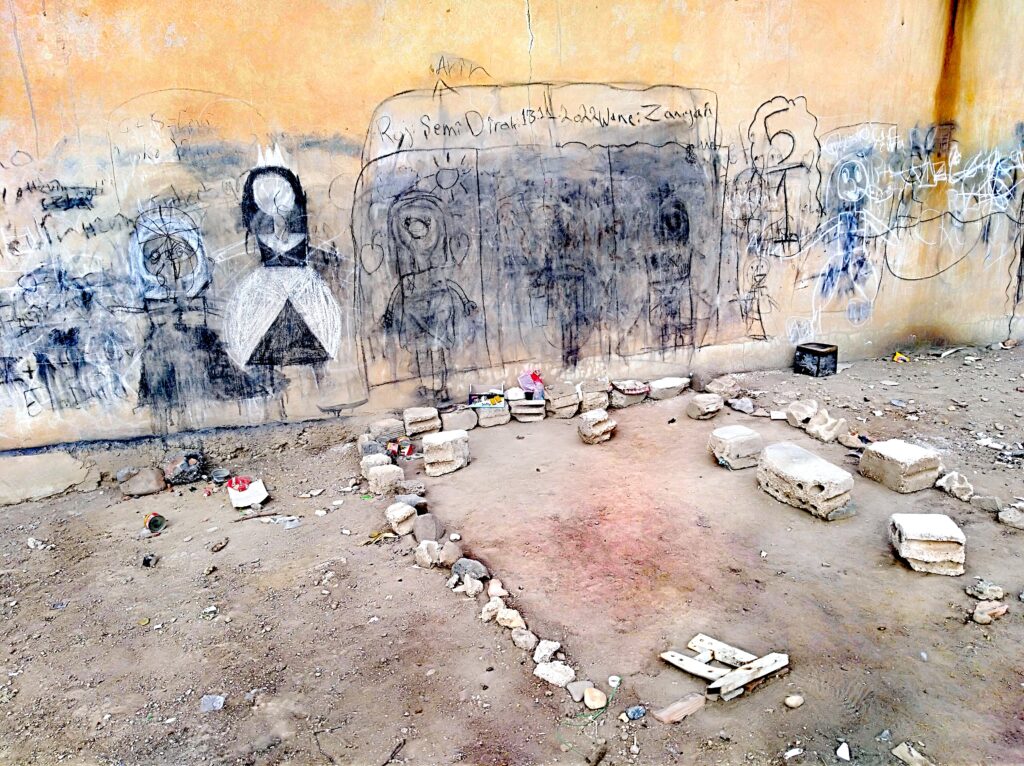

On the way back, I decide to change my itinerary a little. I discover, at the bend in the road, lines of stones marking out children’s play areas, old tins that serve as furniture and crockery for these miniature houses, without walls or roofs but not without a kind of poetry. On the adjoining wall,

chalk drawings bear witness to collective moments of unfurled imagination. A creativity that never fails to move the “believing but not practising” teacher that I am. As I immortalise the scene, two women greet me. When I tell them that I have come from Belgium, one of them rejoices: “My son went to live in Belgium a few months ago!” He has gone to join members of his family who have lived there for a long time. It was my turn to ask questions and realise that he lives in the Burning City (Liège), on the heights of the Pierreuse district, of which I am particularly fond. There are times when the world is definitely a small place. We both rejoice at this coincidence and he invites me to his house for tea.

There I met two young budding mural artists. They are ten and twelve years old, called Rojava and Rojhilat. What a symbol ! We talk about war and migration, our hopes and our fears. I come away with a stronger conviction that, whatever they say, the world is worse off than most of the human beings who inhabit it are.

In short, humanity is, by and large, less rotten than the current state of the planet. I am left wondering what will become of these two young women, where and how they will grow up, what sorrows and joys they will experience. Surely it will be up to them to turn on their shouts and their

weapons to make possible, beyond the state borders that date back to colonisation, unconditional respect for women, life and freedom!

The day after the funeral, on Tuesday morning, I went with my colleagues to another tribute, attended by more than a thousand people. The speeches shouted anger and determination to continue the resistance, against all odds. They proclaim, loud and clear, that fear is absent from

their bodies. Several speeches highlight the dedication of the guerrillas in northern Iraq and the struggle of Iranian women. A group of teenage girls walk past the audience, waving flags and chanting “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi”, which is echoed by the crowd. This experience of Rojava, which wants to go beyond the nation-state model, the heroic guerrilla battles in the mountains of Iraq and the savagely repressed mobilisations in the streets of Iran, are all ONE. The same struggle, the same desire to live a dignified life, the same cry for women’s freedom. The same critique and rejection of a capitalist modernity that inexorably destroys the diversity of life.

Diego del Norte