This article was published in The Region

“Everything was green before,” sighs a young peasant from Sawidiyah, a small Syrian village at the banks of the Euphrates near Tabqa’s massive dam. “Now it should be the season, but the crops are lost, because of Turkey cuts the water, preventing the production of electricity. For us here everything is linked to the agricultural sector. If there is no agriculture, there is no more work. ”

Around him, the vast plains are arid, with only a few rare green plots break the pale brown dry land that stretches far to the horizon. Ahmad Soulayman, head of the economic sector of Tabqa town, bends over and grabs a handful of young shoots that have become brittle twigs, which he crumbles into his hand.”Around Raqqa it was a deserted area before. After the creation of the dam on the Euphrates, the living conditions of the inhabitants have improved. It has been a hope for society. But we are currently facing many difficulties: the water level is too low. It’s a drought. This also impacts the production of electricity. Suddenly the irrigation will stop because the electric pumps cannot work. Even the drinking water stations can no longer work, we will have to go and get water elsewhere and bring it with tanks because there is no reserve of drinking water in each village. Because of all, the incomes fall, and the standard of living degrades. ”

From the top of Tabqa dam, the Euphrates is a blue ribbon bordered with green, tearing the desert lands that surround it. Responsible for the three dams on the Euphrates; Al Hurriyah, Tishrin and Tabqa, Mohammed Tarboush explains the reasons for the water scarcity. “According to international laws, the flow of the river should be 500m3 / sec. But now, Turkey lets pass only 200m3, sometimes even 100m3. The Tishrin Dam was liberated [from IS control] on December 27, 2015. Since then, Turkey has been limiting the flow. That affects the electricity production. The second consequence is the drop in the level of available drinking water for the entire region. It is the agricultural sector that is most affected. The administration has authorised 200m3 for irrigation. But currently, only 50m3 can be distributed. ”

An agreement was signed in 1987 between Turkey and Syria, guaranteeing that the former let of 500m3/s of water flow, except in case of “necessity”. But already at that time, Turkey was threatening to act on the flow of the river if Syria maintained its support for the PKK, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. Today, it is carrying out its threats, unable to tolerate the developments of a political project theorised by the imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan at its borders, whose political pillars are the democracy, the emancipation of women and the ecology.

And it is hardly possible to act. “As a riparian country in the upper Euphrates, Turkey contributes 94% of the flow of the river and Syria only 4%. Francoise Rollan explains in an article dating from 2005.

The low flow of the river limits the electricity production. Mohammad Hamoud, an electrical engineer at the Tishrin dam, said: “It is not possible to have power 24 hours a day because the flow of the river coming from Turkey is not stable. The demand for electricity is higher than what we can produce with the flow coming from Turkey. If it was enough, we could generate enough current for the north of Syria with the three dams, enough even for half of Syria.”

As a result of the shortage, in the big cities of northern Syria, the din and acrid fumes of generators, that mitigate the lack of sufficient electricity production, pollute the atmosphere several hours a day with consequences for public health that have yet to be evaluated.

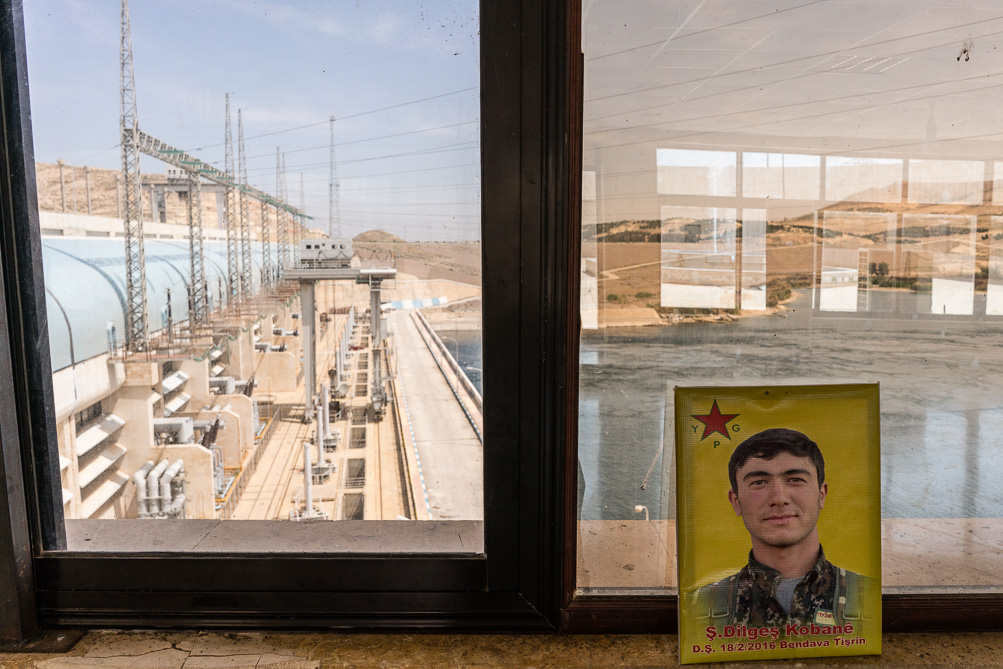

In addition to the low flow of the river, the dams were damaged during the clashes between the IS and the Syrian Democratic Forces. In Tishrin and Tabqa, the walls riddled with impacts and the collapsed ceilings bear witness to the violence of the fighting. “When the IS left, they tried to burn down the control room, the heart of the dam. We repaired it. But spare parts for repairing turbines cause a big problem. We can not find them here, we need Europe, China (Alistom, Schneider). ” In Tabqa, two out of eight turbines operate, in Tishrin, sometimes two out of six works, but, 12 hours a day only.

In addition to the low level of water available for irrigation, power cuts have a devastating effect on agriculture. “Irrigation stops because the electric pumps cannot work. Even drinking water stations can no longer operate, we have to bring water in tanks because there is no reserve of drinking water in each village. In the Rakka region, 113,000 hectares of agricultural land will suffer from lack of water. The regions of Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo and Idlib are also affected, “explains Ahmed Soulayman.

All these areas are crossed by large canals where the drawn water is used for irrigation. Some installations were damaged during the war against IS.

Abu Haydar, who farms land around Sawadiyah, adds “In addition to all of this, it has hardly rained this year. ”

Beside him, Abou Fareer, a farmer, is angry: “All agricultural activities have stopped, there is no water, while we need irrigation working continuously. Water should not be used in political conflict and war. In doing that, it is not the political parties but the citizens who are punished, as well as animals, trees, stones, agriculture. All agricultural products are destroyed, dried up, because there is not enough water, neither for agriculture nor drinking. We just want to live; we do not ask for comfort. ”

Today, as the snow is about to melt upstream of the river, the inhabitants of the Euphrates fear that Turkey will open the flow in an attempt to provoke floods. A scenario that does not scare Mr Hamoud. “Turkey has already tried to open the floodgates” smiles the engineer, “but our dams can take much more than that.” Summer soon coming raises also fears of the evaporation of a large amount of water, resulting in an even lower flow.

The same words return in the mouth of Mohammed Tarboush and Ahmed Souleyman: “Nothing can be done, but to appeal to international law. ”

Beyond the current urgency of the administration, one of the long-term challenges of the autonomous administration of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria will also be to rethink agricultural production. The intensive monoculture model promoted by the Assad regime for decades is not adapted to desert regions because it consumes a lot of water and requires permanent irrigation. And it seems unlikely that Turkey, which seeks to destabilise the autonomous administration, make the slightest gesture of appeasement.